Normally, January and February are slower months in a publisher’s schedule, allowing more time for manuscript reading, planning, and at least snatches of the daydreaming upon which our industry—or at least this press—depends. This has not been the case this year. This has been the busiest first couple of months of a calendar year I can remember. Indeed, I sometimes have trouble remembering what month we’re in; this past Tuesday I wrote down the date as November 25th and didn’t catch it for several hours: November felt right to me. That it is already the last day of February leaves me fearful of drowning, as I know what the coming weeks and months bring.

I start each week writing down on a fresh gathering of pages in my Midori notebook everything that’s on my plate, whether it be editorial, publicity, administration, correspondence, or something tied with the bookstore, a list that often runs over 2-3 pages and which I’ll be lucky to get through a quarter of by the time Friday rolls around. As if Friday marks the end of anything. Of late, the list is longer the following Monday than it had been the previous. There are emails that have been sitting for weeks, that I dutifully re-enter so as not to lose sight of; manuscripts that accumulate in daunting digital piles, to be read and edited both; contracts that need negotiating; publicity and marketing lists that need doing; copy that needs approval; pitches that need to be made; and this barely scrapes the surface of it all. Despite these efforts things slide out of sight and mind, buried pages deep in my inbox, until they resurface in a burst of panic when I’m trying to go to bed. We do our best; we do a lot; often, it doesn’t seem good enough.

There’s been a lot of talk recently across various magazines and Substacks about the crisis of independent publishing, perhaps the most relevant being the series of posts about the demise of New Star over at Ken Whyte’s excellent SHuSH Substack. But what no one seems to want to acknowledge is how much work publishing has always been, and that it has become increasingly more so. Canadian publishers have seen their market access decimated by decisions not of their own making, which has made them more reliant on funding that has, increasingly, become via inflation or cutbacks or changes in funding priorities inadequate to the task at hand. As a group, I’ve never known a harder-working bunch than those who keep Canadian independent publishing afloat. Every book we produce and promote strikes me increasingly as a minor miracle.

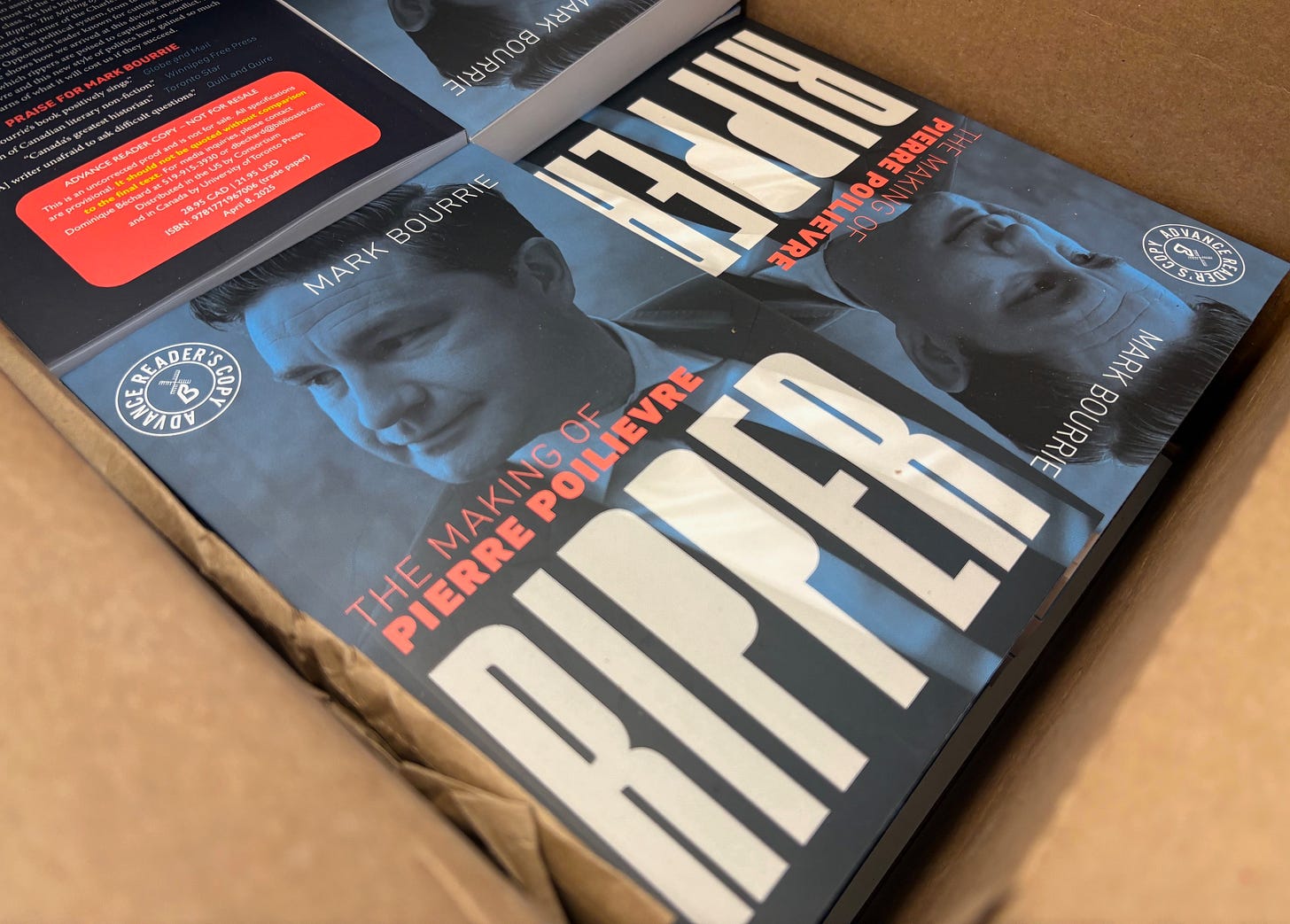

I’m lucky to have such great staff, who’ve stepped up to cover some of the obligations normally on my plate. Dominique and Emily have just returned from Denver, where they attended the American Bookseller Association’s Winter Institute, pitching our books to independent booksellers for days. It’s one of my favourite events of the calendar year, filled with many of my favourite people, and one of the biggest investments we make in our books each year in the United States. It’s worth every penny, and every bit of sleep deprivation. The week after next Vanessa will be taking my usual place at the London Book Fair to meet with agents and publishers and translators and the occasional author: it coincides with the London launch of Alice Chadwick’s Dark Like Under, which Vanessa signed on for June publication in North America, which makes me even more pleased that she’s able to go in my stead, though I am saddened by the fact that it means I will miss meeting with my international cast of regulars. Ashley’s been bailing me out preparing reports for an Ontario Arts Council grant due next week, corralling me into making awards submission decisions, and aiding Vanessa with a monster index for Mark Bourrie’s Ripper: The Making of Pierre Poilievre, among many other tasks that few may notice but without which nothing here would work as well as it does.

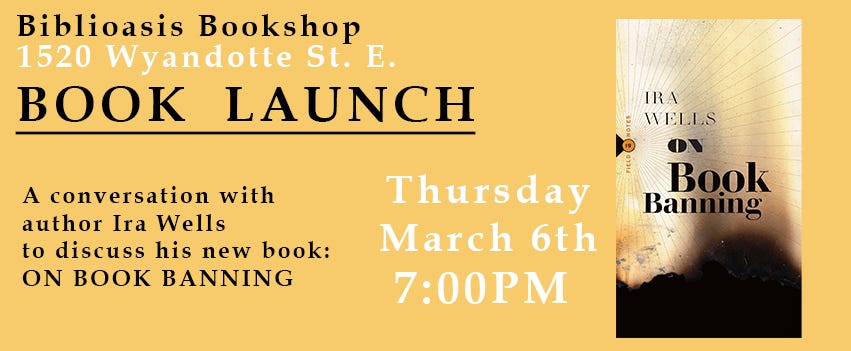

David and Nora have been busy mailing off review copies and direct orders, and Ahmed’s been busy managing all of the publicity for the launch of Ira Wells’s On Book Banning, which has seen exceptional first-week coverage, including interviews on Tara Henley’s Substack, Paul Wells’s Podcast, as well as other coverage at Quill & Quire, the Miramichi Reader, a sold out TPL launch, and much more. All while he lays the ground for the launch of one of our most important novels of the season next week.

Below, please find a short excerpt from the opening pages of Ira Wells’s On Book Banning, which among many other things offers an attempt to “sharpen” the arguments about why books matter. It is, to my mind, another minor miracle of a book.

Dan Wells,

Publisher

Introduction: The New Censorship Consensus

In the spring of 2022, the principal of my children’s elementary school told a group of parents gathered to discuss a library audit that she wished she could get rid of “all the old books.” The bulk of the library’s holdings were, from her perspective, too Eurocentric, too male, too heteronormative. I understood these concerns, which were broadly shared among parents and teachers. Still, the prospect of liquidating several thousand library books struck me as obviously wrong—offensive not only to me personally, but also to the liberal democratic values that (however shakily) underpin our society.

I wanted to say something, but quickly checked myself: Was there not a strong chance that my opposition to removing these “harmful” books would be taken as closet racism? Or that my defense of “liberal values” in this context—a children’s library, with its tiny chairs and animal posters—would come off as patently absurd? I briefly imagined how foolish I might appear—holding forth on democratic ideals like some sad imitation of Gregory Peck or Henry Fonda, everyone around me curling their toes with embarrassment.

Then the moment passed, the meeting broke up, and I was left chewing on my questions: What was so special about a bunch of old books? Were they, in fact, worth defending? Or was my fondness for these antiquated objects a product of my own nostalgia or upbringing—a sign that it was me who was antiquated?

It’s true that I grew up in a bookish household, although I was not a bookish child. There were years of sports, video games, and adolescent hijinks of a tame, middle-class variety, years in which I had no career aspirations beyond making the NHL. Eventually, I found myself yearning for a more literary life, which led to the study of English. In graduate school I crossed paths with extraordinary readers—including a roommate who once read a novel while tying his shoes: He laced up one shoe, noticed a book that interested him, read it cover to cover, then laced up the other shoe and went about his day.

I read slowly by comparison, but voraciously. My job now involves teaching novels and short stories to enthusiastic university students, many of whom are budding bibliophiles; at home, I’ve read aloud to my own children almost every night for more than a decade and will keep doing so until the audience dries up. Many of my friendships were initiated or solidified over the giving or receiving of books, and I have now accumulated more than I might reasonably read in my lifetime. Somewhere along the way, I came to think of these objects as self-evidently valuable. I had lost (if I ever really had) the arguments to explain why books matter, and why the banning and destruction of literature is so odious and socially corrosive.

It’s time to revive and sharpen those arguments. Book censorship is on the rise. We’ve all seen the news stories—the frequent headlines about book banning in schools or public libraries, about the takeover of school boards, about novels that are no longer teachable on university campuses, publishers pulling or issuing bowdlerized editions of suddenly controversial classics, authors who face cancellation. Not all these phenomena constitute “banning” per se, but they all fall under what we might call the new “censorship consensus,” in which books are called upon to justify their existence through demonstrations of their moral value.

Many people who consider themselves book lovers seem comfortable with the new censorship consensus. Indeed, they no longer need an external authority to tell them which books ought to go. In the summer of 2024, after Andrea Robin Skinner, one of Alice Munro’s daughters, came forward with the story of her harrowing sexual assault at the hands of Munro’s husband (and Munro’s complicity over years in covering up the abuse), readers took to X to declare that Munro had been expunged from their shelves. “I just can’t . . . ,” one user posted, above a photo of a garbage can filled with Munro’s Nobel Prize–winning books. We’ve long struggled with questions about how to frame the art of people who do things we abhor, but it was the lack of struggle that seemed notable in this case—at least among those who had decided that Munro’s work was now trash.

Books have always been challenged, but the current eruption of censorship feels like something new. “Book Bans Continue to Surge in Public Schools,” went an April 2024 New York Times headline, which found that rates of book banning were doubling year over year.* According to PEN America, thousands of book removals occurred in 2023, in forty-two states, both Democratic and Republican. PEN has now identified more than ten thousand instances of books being removed from U.S. schools but is quick to clarify that the true number is likely much higher: One well-known study conducted by the American Library Association estimated that between 82% and 97% of all library challenges go unreported.1 Much of this book banning appears to be fueled by outright bigotry: “Overwhelmingly, book banners continue to target stories by and about people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals,” PEN notes. “30% of the unique titles banned are books about race, racism, or feature characters of color. Meanwhile, 26% of unique titles banned have LGBTQ+ characters or themes.”2

Book bans are as old as the book itself. In my country, state-sponsored book censorship began with the passage of the Customs Act in the first session of the Canadian Parliament in 1867. That Act prohibited the importation of “books and drawings of an immoral or indecent character”; the criminal code further forbade the exhibition of any “disgusting object.”3 The United States outlawed using the Postal Service for “obscene, lewd, and lascivious” material—prohibitions backed by measures including confiscation, customs seizure, civil and criminal prosecution, and police arrests.4

Where book banning once largely involved the legal and disciplinary apparatus of the state, the new censorship consensus works through both state actors and a constellation of special interest groups operating inside and outside of institutions. Their target is libraries: public libraries, in which all taxpayers have a stake, and especially school libraries, which can be uniquely vulnerable due to chronic funding shortages and lack of full-time librarians able to cultivate their collections over time.

Libraries are natural quarry for anti-government organizations, including Moms for Liberty and No Left Turn in Education. Legal challenges against books, of the sort that once banned Ulysses and Lady Chatterley’s Lover from American shelves, are costly and hindered by decades of First Amendment jurisprudence that steadily broadened the sphere of expressive freedom. Libraries, by contrast, are soft targets. Any citizen can mount a challenge. The instructions for doing so are often posted on the library website. Today’s lawmakers are still more preoccupied with the dangers of online speech than with book bans (although that is rapidly changing in some quarters).

We should be clear on the stakes. When parental rights organizations attack libraries, they are attacking one of the last public institutions committed to intellectual freedom. While it’s true that more books are now available online, we court disaster by assuming that the internet—which is volatile and ephemeral and frequently weaponized against users across the globe—has replaced libraries as key intellectual infrastructure for liberal democracies.

Battles over book banning are especially contentious in school libraries, for obvious reasons. We compel children to attend school, and kids are more impressionable, so materials must be “age appropriate”—an inherently debatable category. Those who would cleanse the school library frame their efforts as an appeal to save children from harm.

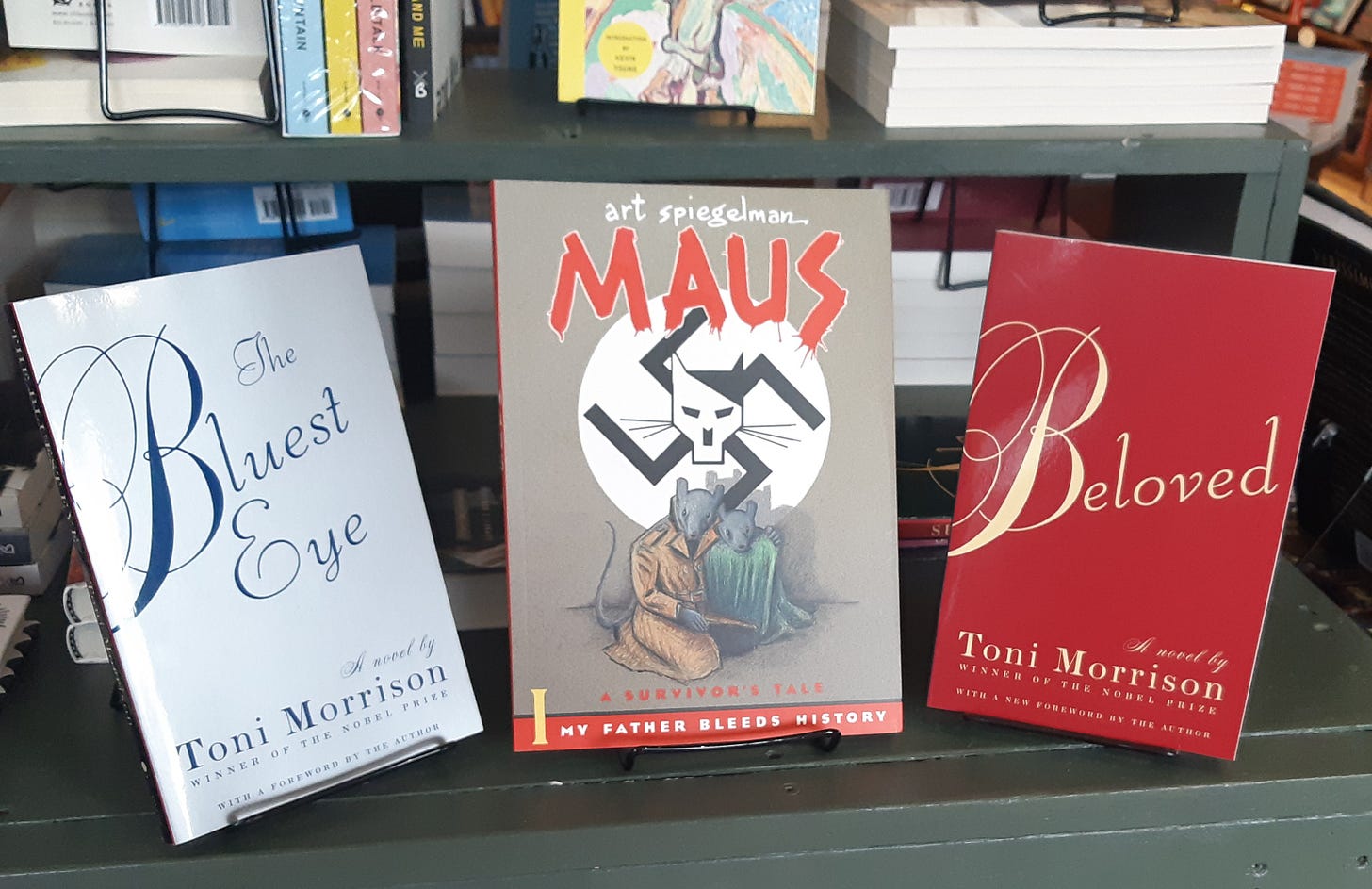

Beneath the surface of these disputes lies a deeper conflict over our national and communal history. One reason why book banners so frequently attack historical fictions—including Maus, Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel about his father’s experience as a Holocaust survivor; Beloved and The Bluest Eye, Toni Morrison’s haunting novels of American racial trauma, and countless other texts at the intersection of race and history—is that the banners are fighting for control of our collective past. At the same time, in seeking control over the narratives that children will carry into adulthood, the banners are fighting for their vision of the future. Attacks on school libraries are, among much else, future-oriented attacks on liberal democracy and its vital institutions.

*Similar trends have been playing out in Canada. According to a report from the organization Freedom to Read called “A Rising Tide of Censorship,” Canadian libraries reported 118 “intellectual freedom challenges” in 2022–23, which represented a 50% increase from the previous year, which had itself seen a 50% increase from the year before that. These numbers, the report warned, “likely represent a very small portion of actual censorship efforts in Canadian libraries.”

In good publicity news:

Ira Wells, author of On Book Banning, was featured in a number of outlets for Freedom to Read Week:

a Q&A on Lean Out with Tara Henley

an interview on The Paul Wells’ Show, both as a podcast episode and as a video on YouTube

a review in Buried In Print: “Timely and relevant, balanced and engaging.”

an interview on The Commentary

a review in The Miramichi Reader: “Both important and urgent, its value enduring well beyond the annual week when we decry the banning of books.”

Baldwin, Styron, and Me by Mélikah Abdelmoumen (trans. Catherine Khordoc) was reviewed in That Shakespearean Rag: “A valuable examination of certain points of dissension or disagreement ongoing in our culture.”

The Passenger Seat by Vijay Khurana was excerpted in LitHub, and reviewed in Books + Publishing: “An unusual and deftly written literary thriller.”

Dark Like Under by Alice Chadwick was reviewed in the Daily Mail: “An unpretentiously elegiac novel, it hymns nature’s solace and the power of human connection with memorable grace”; the Guardian: “[An] ambitious and affecting debut . . . Dark Like Under is impressively subtle, sensual and sympathetic.”; and in the TLS: “Gripping . . . [a] mature, glorious book.”

Alexandra Alter, “Book Bans Continue to Surge in Public Schools,” The New York Times, April 16, 2024 https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/16/books/book-bans-public-schools.html.

Kasey Meehan and Jonathan Friedman, “Banned in the USA: State Laws Supercharge Book Suppression in Schools,” PEN America, April 20, 2023.

Brenda Cossman, “Censor, Resist, Repeat: A History of Censorship of Gay and Lesbian Sexual Representation in Canada,” Duke Journal of Gender, Law & Policy 21.1 (2013).

See Rosen v. United States (1896), qtd. in Jennifer Elaine Steele, “A History of Censorship in the United States,” Journal of Intellectual Freedom and Privacy 5.1 (2020): https://journals.ala.org/index.php/jifp/article/view/7208 /10293.