Second verse same as the first . . .

The introduction to Ray Robertson's Dust: More Lives of the Poets (with Guitars)

Ray Robertson’s latest book of music writing is a warm repository of discovery. I found it hard to get through a chapter without turning to my headphones to hear for myself what Robertson describes so vividly. Much of the music in this book is music I’ve known for years, and I loved that experience: of listening to something familiar for the first time.

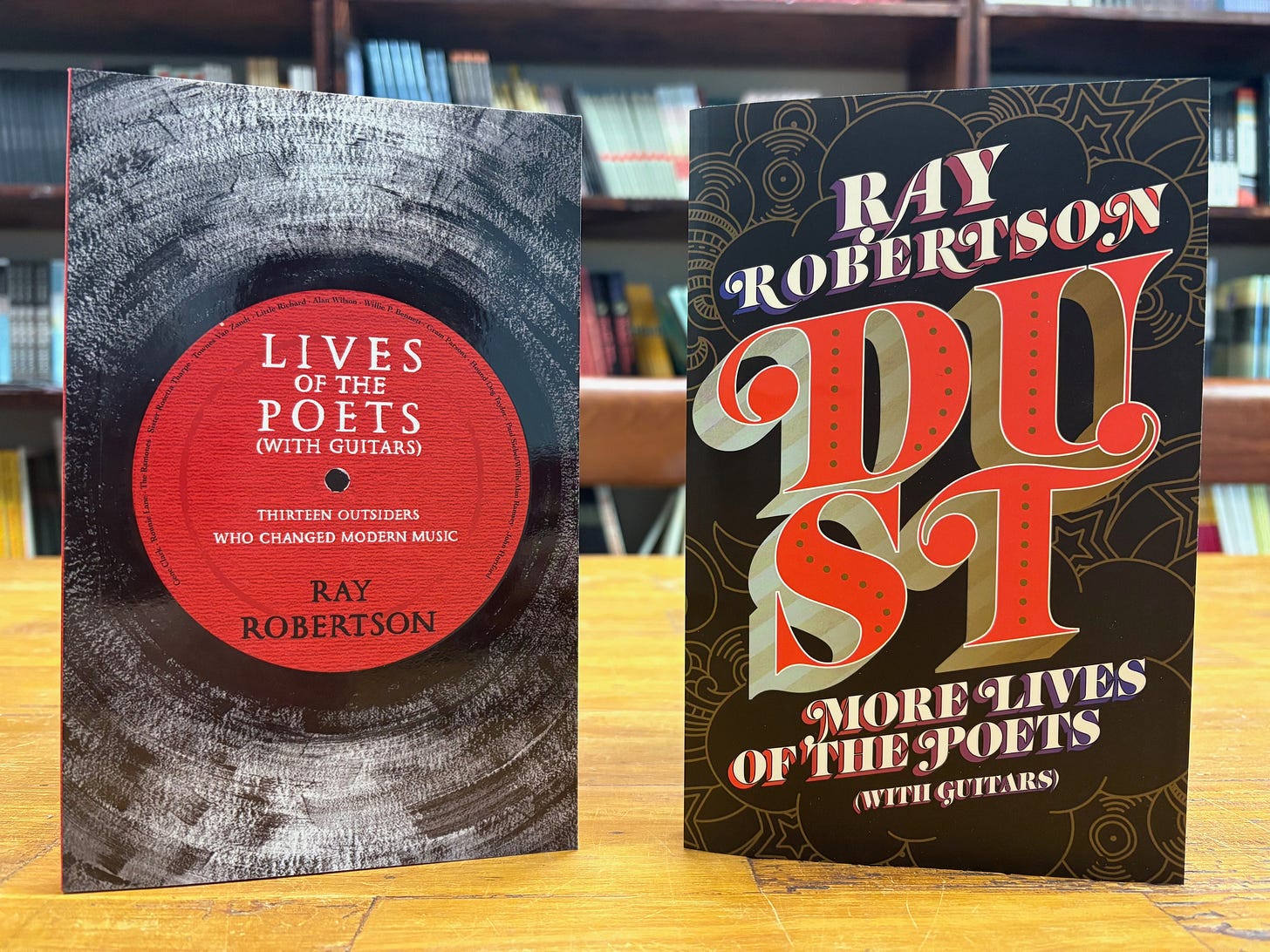

Dust: More Lives of the Poets (with Guitars) is the long-awaited follow-up to 2016’s Lives of the Poets (with Guitars), and the perfect gift for any music aficionado. As with the first Lives, Dust is made up of a dozen portraits of musicians Robertson loves (all of them artists who sound distinctly like themselves)—from Alex Chilton, to Muddy Waters, to Handsome Ned, to The Staple Singers . . .

It’s a thoughtful book, too, full of the paradoxes involved with being both painfully human and the maker of something transcendent. Though mainly a collection of “musical cheerleading,” it’s also peppered with smart, funny digs. I chuckled when Nico’s famously-excruciating The Marble Index is described as “a half hour in hell with Nico as your somnolent tour guide.”

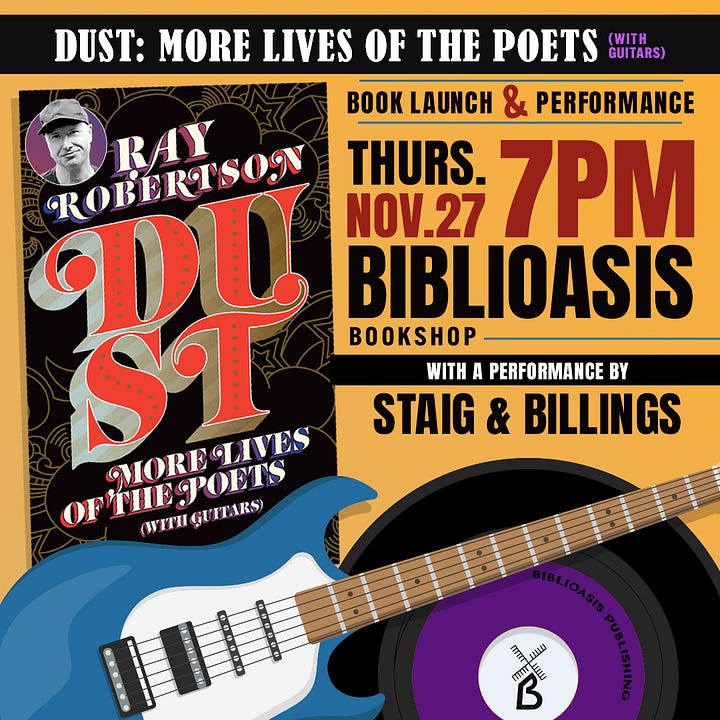

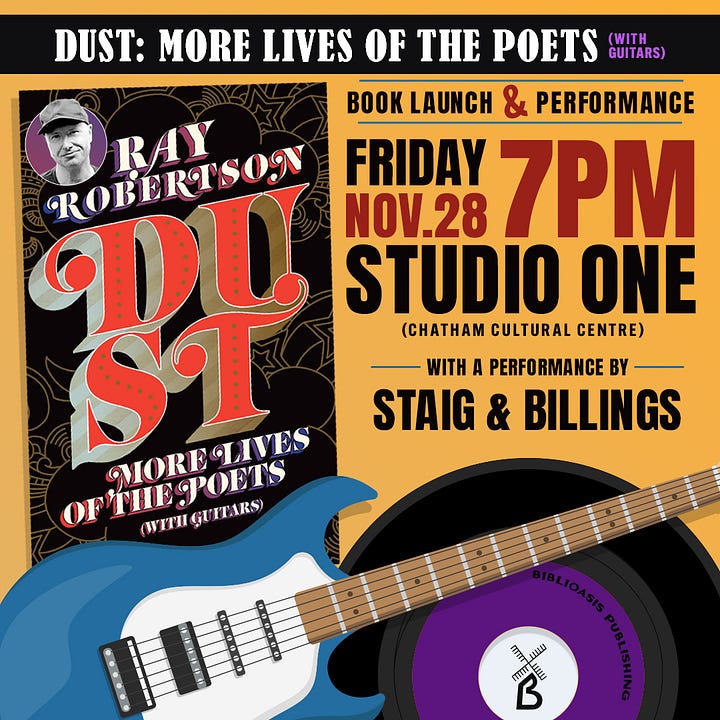

Ray Robertson has two events lined up next week. Accompanying him on the road is folk duo Staig & Billings, who will be covering one song by each of the twelve musicians profiled in Dust. It’s sure to be a good time.

Windsor: November 27 at 7PM, Biblioasis Bookshop

Chatham: November 28 at 7PM, Studio One (Chatham Cultural Centre)

In today’s Bibliophile, we’ve included the introduction from Dust, which provides a glimpse into Ray Robertson’s selection and approach.

Dominique Béchard

Publicity & Marketing Coordinator

Introduction from Dust: More Lives of the Poets (with Guitars)

by Ray Robertson

Second verse same as the first . . .

With one main difference: there won’t be a third. I couldn’t stop writing about music if I wanted to—and why would I?—but Dust: More Lives of the Poets (with Guitars) is both a sequel to its predecessor and the last of its kind, at least as written by me. In V. S. Pritchett’s The Living Novel, one of his many collections of indispensable literary essays, he baldly admits to being “too idle and specific in my enquiry to call myself a critic,” maintaining instead that he is merely “an ordinary reader who has some private axe to grind.” Me, too, but as an ordinary listener.

I’ve always been a not-so-secret proselytizer for whatever has given me those too-rare glimpses of joy, profundity, and occasional transcendence that make human existence more than the sum of its oftentimes puzzling parts. If my musical appreciations have been predicated on any critical theory, it is simply this: If I believe something is uncommonly good or interesting, I’m going to try to help the reader hear and see what I hear and see in the hope they’ll listen for themselves and think so too. Granted, it’s not much of an aesthetic, but that’s how much of the criticism I gravitate toward operates—experientially. Besides, I’d rather be myself and wrong than correct and somebody else.

It may be that, as Swift (about whom Samuel Johnson, in his pioneering Lives of the Poets, wrote so superbly) said, “To endeavour to work upon the vulgar with fine sense is like attempting to hew blocks with a razor,” but a lifetime of reading about music certainly inspired me to try my own hand at music criticism (or, if you prefer, musical cheerleading). The best of these writers—Lillian Roxon, Nick Tosches, Lester Bangs, Nick Kent—dependably delivered the goods regarding what music is worth obsessing over, but they did so in styles demonstrably their own and in the context of the life and times of the musician or musicians under consideration. They weren’t writing minibiographies (lacking the inclination, aptitude, and energy of the biographer, neither am I), but they did highlight, when appropriate, aspects of the musicians’ lives to help the reader better understand their music and their careers.

Every one of the artists in this book has been, and continues to be, important to me—and not just musically. The music is where the fascination began, but it’s not where it ended. Alex Chilton’s ongoing tussle with commercial success; the relationship between unhappiness and creativity in the music of James Booker; Nico’s intrepid, if doomed, self-reinvention; the gap between aesthetic bliss and worldly consequence in the Staple Singers’ story; Captain Beefheart’s dogged, dictatorial individualism; Handsome Ned and the lure of the local; Duane Allman and the dictates of fate; Lee Mavers’s paralyzing perfectionism; the alternately injurious and inspiring Manichaeism of Duster Bennett; the supernova-like artistic extinction of Danny Kirwan; Nick Drake and the vagaries of fame; Muddy Waters and the exhaustion of form: each of these stories is grounded in great music but also imbued with tragedies and trials and quandaries and paradoxes often typical of the artist’s life—in some cases, quandaries and paradoxes as absorbing and enriching as the music itself.

And when the subject is music and the tools of your trade are black squiggles on a white page, metaphors, similes, and analogies are some of your best friends, especially when, like me, the writer in question isn’t also a musician with a head full of technical terminology. Every musician is a potential Orpheus, charming the beasts and setting the stones dancing, but short of the sound itself, we have, for instance, Sam Phillips’ observation that the first time he heard Howlin’ Wolf’s voice, he thought, “This is where the soul of man never dies.” Writing about music might be like dancing about architecture, but so what? Dancing is rarely ever a bad idea.

And speaking of words, a few quick ones about the words “poets” and “poetry.” Songwriters use words much as a painter employs colour—rhythm, sound, and strategic word placement conveying a song’s “meaning” more than any limp literalism. The best Muddy Waters music is poetic, but the lyrics to “I Can’t Be Satisfied” or “I’ve Got My Mojo Working” all on their own aren’t poetry. There’s more poetry in the five-second, introductory Oh, yeah, Oh, yeah growl and giddy- up of “Mannish Boy” than there is in any Bob Dylan or Joni Mitchell lyric. Every one of the musicians in this book is an electric poet—not because of the words they sing, but because of how those words are sung and because of the music that makes those words so memorable. Poems come with their own built-in melody, meter, and structure. Song lyrics require the magic of music to sparkle and inspire and swing. And whether it’s words on the page or music in our ears, swinging is what we’re after.

Even though most of the musicians celebrated in this book and in its predecessor are dead. Despite the fact that the conditions—economic, social, technological—that helped make their music possible have changed almost beyond recognition. The title of this book is taken from a Danny Kirwan song, the lyrics of which were written several decades earlier by the English poet and sailor Rupert Brooke, who died of blood poisoning in World War I. It’s sad, it’s beautiful, it is what art can do that life all on its own cannot: praise. “When we are dust, when we are dust!” Yes. Undoubtedly. But listen to how Danny so sacredly sings it. Marvel at how a dead man’s words are wedded to a young man’s music and the world becomes a different place. Who said dust can’t dance?

I had a nightmare once: an LP was playing on a record player, over and over and over, the tone arm of the turntable automatically returning to the beginning of the record as soon as the side was done. Eventually, the record literally ran its grooves out and was unlistenable, useless, dead black plastic. And the entire time, no one was listening.

Does a tree fall in the forest if no one hears it? I wouldn’t know. I was listening to my records.

In good publicity news:

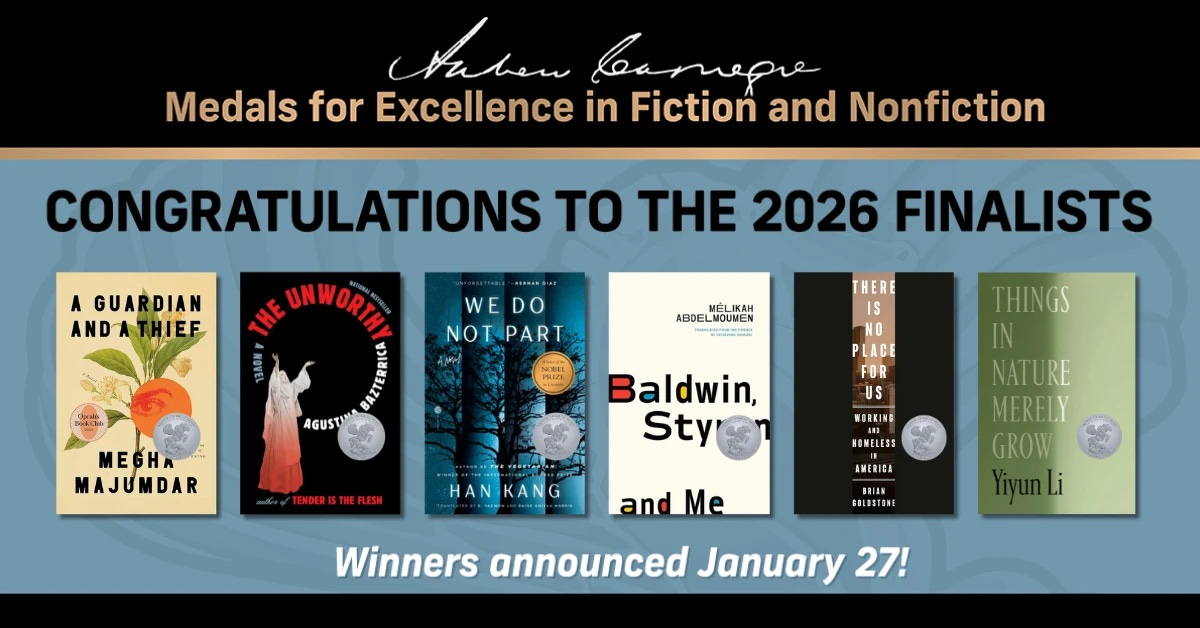

Baldwin, Styron, and Me by Mélikah Abdelmoumen (trans. Catherine Khordoc) has been shortlisted for the 2026 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction! Winner to be announced January 27, 2026.

Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet was reviewed in the Globe and Mail: “Reading a novel by Graeme Macrae Burnet is unnerving because the experience always becomes physical. You slip eagerly into a Burnet book because it feels like a familiar garment—only to realize that it’s a (metafictional) straitjacket, sewn from what are alleged to be found diaries or true historical accounts or actual case studies, or even all three.”

Old Romantics by Maggie Armstrong was reviewed in Scout Magazine: “Deeply entertaining, insightful, and thought provoking; as well as being full of dark humour, honesty—and no shortage of sumptuous food descriptions.”

Self Care by Russell Smith was featured in Zoomer: “A genuine page-turner.”

The Notebook by Roland Allen was reviewed in SHARP News: “Allen’s book will inspire those interested in the material to follow his many trails and suggestions. It certainly makes for enjoyable and informative reading.”

Kind thanks!